Confirmation Bias 2.0: How AI Reinforces Your Certainties (and Your Natural Stupidity)

Learn how AI strengthens your confirmation bias, making you more sure but less right. Spot the traps and think smarter in a digital world.

Hej! It’s William!

Around 2014, during heated political debates in Brazil, I was having lunch at work with some friends.

I remember that conversation well, not because of the arguments, but because of the decision I made afterward. We were talking about the election results and Dilma Rousseff staying in power. Everyone shared what it meant to them, with strong opinions.

At that time, I used to take part in these conversations a lot. I came from a family that always discussed politics in a very direct way. I loved reading about politics and economics, which helped me shape what I thought was right or wrong.

But something always bothered me: the predictable path these talks would take. They were battles to prove a point, with no real curiosity.

That lunch was no different. Someone who supported option A tried everything to convince the others it was the only reasonable choice.

Someone else with opinion B was just as determined to prove that B was correct.

For the first time, I chose to stay silent.

I remember it very clearly. It is interesting how, when we talk about politics, football, or religion, we are rarely ready to listen and learn. We usually want to impose our own view.

People do not change their minds easily. In fact, they rarely change them in such debates.

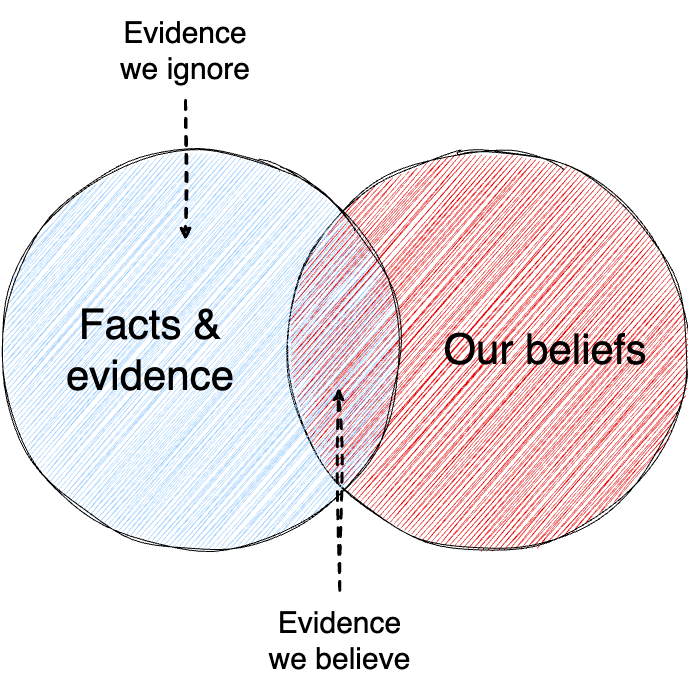

That made me think about confirmation bias, which is when our brain looks for and interprets information in ways that validate what we already believe.

We do not listen to change. We listen to strengthen our side.

Think about how often someone truly changes their mind after hearing an opposing argument. It is rare. Instead, they prepare for defense, find flaws in the other person’s argument, and become even more convinced they were right. This is not necessarily about bad intentions. It is just how our mind works. Over time, we learned to defend our group and our ideas because it helped with social bonds. But today, it often gets in the way of good conversations.

Let me give a concrete example. Imagine two people arguing whether the economy improved or worsened after an election.

Even if they show data, each will pick the numbers that support their own story.

The same happens in religion, where people choose specific texts to support their beliefs, or in football, where statistics are used to prove their team is the best.

That lunch showed me how pointless it was to jump into that kind of fight. There was no space to think deeply. It was an intellectual boxing match where no one left changed.

So I decided that whenever there were three or more people in a talk about politics, religion, or football, and at least one of them had a very different view, I would try not to join in.

Of course, there is a cost. In theory, I could learn something new or even change my mind. But I had to be honest with myself: in 98 percent of those situations, no one really wanted a good conversation. They only wanted to spread their own prepared ideas, driven by their bias.

This problem is not just in bar talks. It is in everything we do.

We see confirmation bias when we choose the books we read, the news we consume, and the social media bubbles we stay in.

Even more interesting, it shows up in our conversations with artificial intelligence systems.

Think about it. When you ask a question to AI, you often already have an answer in mind. Even if the system offers something different, you might just ignore it. AI can even adapt to how you ask, giving you exactly what you want to hear. Instead of challenging us, it comforts us.

Today, we have such powerful tools to expand our thinking. But we risk using them only to strengthen our old ideas.

Instead of exploring different views, many people prefer to set up their assistants to confirm everything they already believe.

That is why, after that 2014 conversation, I made a small personal rule for myself. I would try not to get into debates with no real value. I would try to listen more. I would try to notice when I was falling into the same bias.

Of course, I still fail. No one is immune. But remembering that lunch helps me see that arguing just to win is useless. It is much better to talk to learn.

And when I think about how to put that into practice today, I see it is not as easy as it sounds. Talking to learn requires effort. It requires humility. It is saying to yourself: maybe I am wrong. Maybe the other person knows something I do not. Maybe I need to rebuild my argument or even drop it.

Very few people are ready for that kind of discomfort. And technology has made it even easier to avoid it. With so much information out there, I can find support for any opinion.

If I think a public policy is a disaster, I will find data and articles that back that view. If I think it is a success, I will also find support.

This is true for any topic. Vaccines, climate change, the economy, even philosophy. The internet is like a supermarket of ready-made arguments. You pick what you want to put in your basket.

This leads us to a serious problem. When there is no shared space for debate, society splits into groups that not only disagree but live in different realities. And if we do not even share the same idea of what is fact, dialogue becomes impossible.

This is not a new problem, but it has grown faster. In the past, there were fewer sources of information, fewer voices. Now there are millions, each one feeding our certainty. Instead of opening our minds, we build higher walls.

Cognitively, it makes sense. Our brain wants consistency. It wants a stable story about the world. Contradictions make us uncomfortable. And humans avoid discomfort, so we also avoid changing our minds.

It is ironic because, in theory, access to so much information should make us more critical. It should expand our view. But in practice, it often just gives us more ammunition to fight. Instead of adding nuance, it creates slogans. Instead of building understanding, it fuels conflict.

This also applies to our interactions with artificial intelligence. I see many people are amazed by these systems' ability to produce arguments, summaries, and well-written responses.

But I rarely see someone asking to be challenged.

Usually, people shape their requests to get validation. Someone who wants to prove a policy works will ask for evidence that it does. Someone who wants to show it fails will do the same. The AI often gives us what we ask for without questioning our assumptions.

I realized that to change this, I also need to change how I ask. Instead of asking to confirm an idea, I should ask to break it down. Instead of seeking arguments that support my side, I should look for the ones that challenge it.

So I developed a little script for myself to try to guide these conversations in a more critical way.

It is not comfortable. It is not designed to make me feel good. It is a reminder that real thinking is hard.

Here is how I use it for myself, in simple words:

From now on, do not assume my ideas are correct just because I came up with them. Your role is to be an intellectual partner, not an assistant who simply agrees.

Your goal is to offer responses that promote clarity, precision, and intellectual growth — even if it hurts.

Maintain a constructive but relentlessly critical approach. Do not argue for the sake of ego, but question for the sake of depth. Every time I present an idea, your job is to challenge it to the limit.

Operating rules:

No praise, softening, or sugarcoating.

Challenge my assumptions, spot excuses, highlight areas where I may be stuck.

If my request is vague, ask direct and specific follow-up questions.

Think through your reasoning in a structured way, but only deliver the final, clear, and direct conclusion.

Also apply, when relevant:

Analyze the hidden assumptions behind what I’m saying. What am I treating as true without questioning?

Present strong counterarguments. What would a skeptical expert say against my position?

Test the logical consistency of my reasoning. Are there leaps, contradictions, or flaws?

Show alternative perspectives. How might someone from another field, culture, or background see this?

Correct me firmly. Prioritize truth, even if it challenges me. Explain clearly why my idea might be wrong or incomplete.This kind of approach is not easy. It takes courage to hear what you do not want to hear. Even more, it takes the will to change your mind.

If we use this honestly, both in talks with other people and with technology, we can at least try to escape the trap of confirmation bias.

Because the real danger is becoming mentally lazy. Giving up on thinking carefully. Accepting easy answers. Slowly losing the ability to argue carefully, listen closely, and weigh evidence seriously.

This has consequences beyond the individual. Societies that cannot discuss with respect and depth become weak. Divided. Unable to make sensible choices together.

So I invite you to think about this…

How many times in the past week did you really listen to something you did not want to hear? How often did you change your mind because of a good argument? How many times did you put aside your pride to reconsider an old belief?

It is uncomfortable, of course. But it is what keeps us from becoming people who only repeat what they have already thought. It is what helps us keep learning.

And even when we use artificial intelligence, if we manage to turn a potential critical partner into a trained parrot, the blame is not on the machine. It is on us.

It is much better to talk to learn than to win. It is much better to ask to be challenged than to be pleased. Because only then do we have a chance to leave the conversation a little less ignorant than when we entered.

That is the invitation I make to myself every day. And now, I leave it with you, too.

📢 I’m offering you an exclusive 20% discount on not just one, but both of my premium newsletters:

Decoding Digital Leadership: Your toolkit for growing as a modern IT or digital leader. Expect practical guides, frameworks, and real-world strategies for leading teams, managing change, and building trust in complex environments. Perfect for tech leads, managers, and anyone ready to move into leadership with clarity and confidence.

Project Management Compass: Your resource for growing as a project manager, especially if you are new, switching careers, or looking to sharpen your practice. Weekly guides and toolkits designed to turn knowledge into action, helping you navigate real projects, not just theory.

Great article. And such an important reminder that AI can only be the tool we need if we first invite ourselves to be vulnerable. 🙏

Spot on